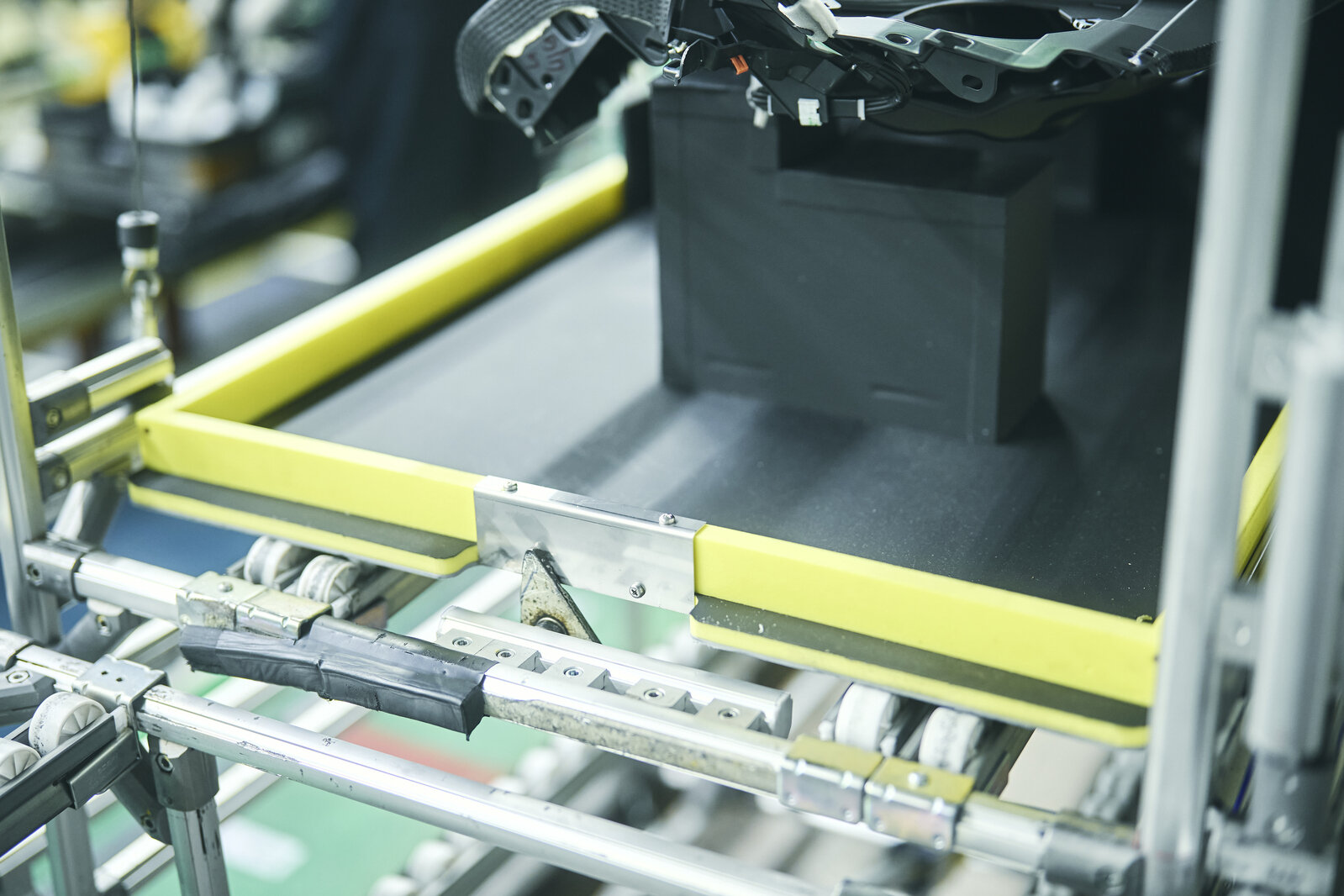

Toyota's Creative Idea Suggestion System makes work more fun and interesting. In this article, we take a look at how the Motomachi Plant's used karakuri--clever mechanical tricks--to create an instrument panel chute.

“Our temporary storage area is overflowing with parts, and the AGVs (automated guided vehicles, used for transporting parts to designated locations) are backed up. How can we possibly get a good work rhythm going…”

Such were the grumblings of technicians working in the instrument panel installation genba, overseen by the Motomachi Plant’s Assembly Section No.1.

The Motomachi Plant faces unique obstacles as it takes on the challenge of high-mix, low-volume production and specialized monozukuri.

“Here, we put together instrument panels for nine different car models. Even within the same model, the parts differ by grade, so we inevitably end up with a large number of components, and our temporary storage areas were overflowing,” says 2NB Team Senior Expert Eiji Nagayama of 2NB Team, Assembly Section No.1.

Part of the reason why workers couldn’t get into a good rhythm was the fact that parts transporters frequently blocked the paths of AGVs, causing them to automatically stop.

These issues were a headache for not only the genba technicians, but also the production preparation group that sets up facilities for new models.

Birth of the instrument panel chute

Eiji Nagayama, Senior Expert, 2NB Team, Assembly Section No.1

Once we decide on something specific that we want, the ideas start coming.

This time, however, we had to start by figuring out the layout, the kinds of things we would set up, and how they would become part of the workflow. That was the hardest part.

Traditionally, parts were kept on shelves within each workbench, to be taken out and assembled as needed according to the production order information. This process was completely overhauled from the ground up, with the necessary parts now coming down the line on trays.

How, then, do you ensure the parts trays are received and returned efficiently?

To solve this puzzle, the team came up with the instrument panel chutes we want to highlight in this article. Let’s start with a video of the system in action:

The entire arrangement uses no power and is instead controlled by karakuri.

At Toyota, “karakuri” refers to ways of automating and improving tasks without relying on electricity, by using simple mechanisms such as gears, springs, and levers. We introduced many examples in a past Toyota Times article.

Before the chutes were put in place, AGVs transported parts from a separate sequencing area*¹ to the preparation process area. Unfortunately, these AGVs had to wait for the parts transporters that frequently criss-cross the plant and block narrow pathways as they stop to supply components. Once they could continue on their way, the AGVs would supply the sequenced parts*², which sometimes left technicians empty-handed.

*¹A place where all of the parts needed for a single vehicle are sequenced into the order in which they will be assembled.

*²Parts sequenced based on the assembly order of each vehicle.

When the team reviewed this entire process, including the stages before and after, the instrument panel chutes were introduced as part of major changes to the layout and flow of goods. The result was that AGVs were no longer needed, which also solved the plant’s traffic jam problem.

When the chutes were first built, the stopper on the upper level that feeds new trays had to be manually released by the technician, with the pull of a lever. From there, however, the system was further improved through creative ideas, with the stopper now released automatically by simply pushing an empty tray down the line when the task is finished. A prime example of “continuous kaizen.”

This mechanism employs a thick fishing line normally used for catching tuna. The stopper release works by linking the vertical movement of the wheeled rack with the action of the weight.

Nagayama

“There was some distance between where you return the tray and the release lever, so we decided to automate that part of the process as well, to eliminate waste wherever possible. Fine-tuning the weight gave us a fair bit of trouble.”

Why karakuri are crucial in cutting-edge monozukuri

Nagayama’s unit is chiefly tasked with building the items requested by work teams seeking to make improvements. Other duties include safety maintenance within the plant, as well as evaluating and improving workplace environments to accommodate increasingly diverse personnel.

When picturing the plants that produce BEVs and other cutting-edge cars, you might imagine that everything is mechanized, with motors powering massive pieces of equipment. However, as Nagayama tells us, the latest technologies make harnessing karakuri all the more important.

Nagayama

Within Assembly Section No.1, our policy is to rely on power as little as possible. Part of the reason is that we change our processes more frequently than other vehicle plants.

If we had to dismantle all kinds of wiring and set it all up anew each time, the work would take us days. With unpowered karakuri, on the other hand, we can move equipment around very quickly.

Since no CO2 is emitted, karakuri-based kaizen is also seen as a meaningful approach toward decarbonization.

The growing importance of creativity in an era of diversity

Nagayama

“The award was 10,000 yen for the chute, and another 10,000 yen for the automatic stopper release. But this time I myself wasn’t involved in the proposal—I had the members who actually got their hands dirty building the karakuri make the submission.

I was glad that everyone could put in their ideas and give them shape. I was also really happy to hear the genba technicians say that we made their work easier.”

Despite humbly claiming that he was only a coordinator, Nagayama was very pleased that these improvements came to fruition. In his younger days, he viewed submitting creative ideas as just another duty, but these feelings gradually changed.

Nagayama

As my creative ideas levelled up, I came to think in terms of benefitting others. Also, in the past we tended to learn by watching how things were done, but in this age of increasing diversity we need to create an environment where tasks are easy for anyone to understand and perform. I feel that creative ideas are essential for establishing such conditions.

Finally, we asked Nagayama for his definition of kaizen.

“Something that rewards persistence. As well as continuing to suggest ideas, I think it’s also important to keep developing the improvements you’ve already made.”