An ongoing series looking at the master artisans supporting the automotive industry. For our 20th installment, we spoke with the mold-polishing master whose mirror-like finishes produced Toyota's first paintless bumpers.

Handwork still plays an important role in today’s car manufacturing, even as technology like AI and 3D printing offer more advanced methods. This series features the craftmanship of Japanese monozukuri (making things) through interviews with Toyota’s carmaking masters.

This article is the first of a two-part feature on the Mobility Tooling Division’s Hideki Kato, who produces plastic part molds with mirror-like finishes. His dedication to his polishing skills lies behind the Crown Sport’s paintless rear lower bumpers.

#20 Hideki Kato, a master of hand-polishing molds for plastic parts

Senior Expert, Mobility Tooling Division, Toyota Motor Corporation Production Engineering Development Center

A master 40 years in the making

Located in Toyota City, Aichi, the Teiho Plant is one of the facilities that designs and manufactures molds for parts such as car body panels and bumpers. In a corner of the plant sits the rear lower bumper mold used for the Crown Sport prototype. Its polished surface gleams like a mirror.

Such molds are used to create parts out of plastics, metals, and other materials. The molds themselves are made by casting or forging steel, which is then machined into the desired shape based on computer data. From there, the surface is carefully polished with grinding stones and sandpaper. This final polishing stage has been taken to new levels by the skilled hands of Hideki Kato.

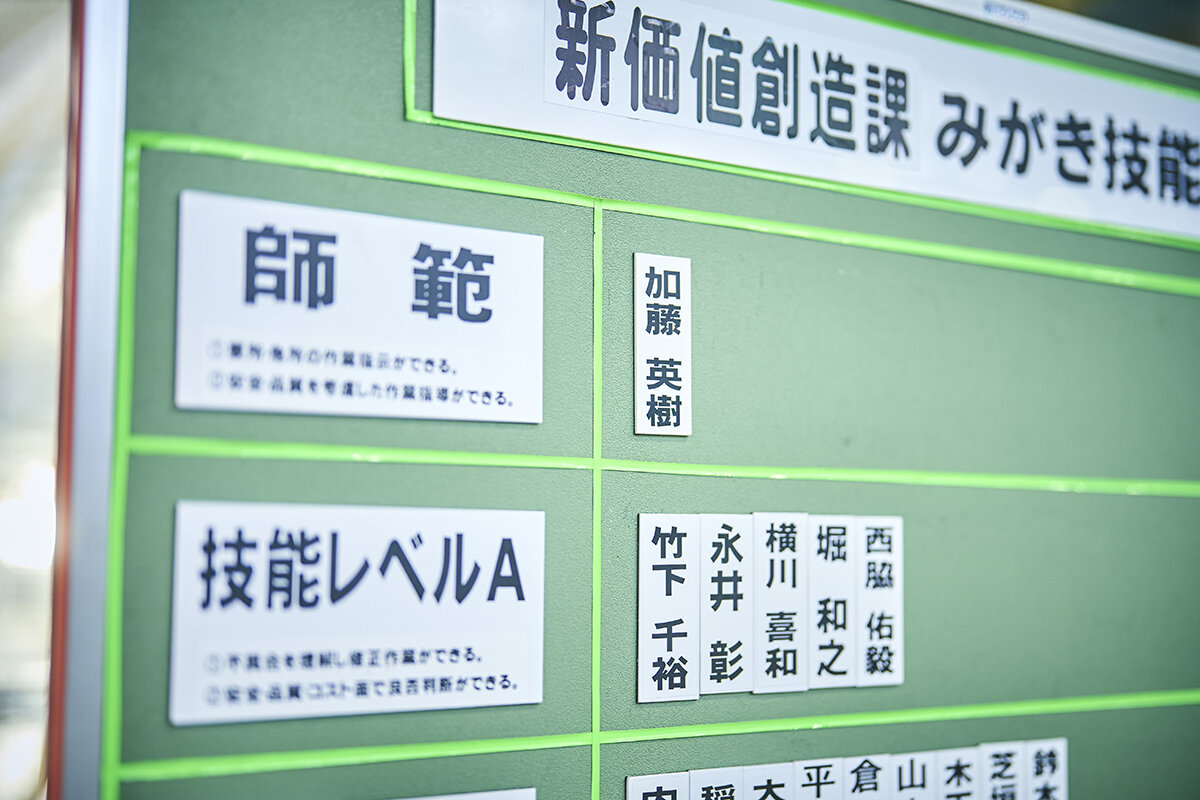

Kato’s polishing skills have earned him the rank of Master Instructor, the highest in the New Value Development Section where he is assigned. He says that reaching this pinnacle of craftsmanship took more than 30 years of experience.

The 57-year-old Kato showed a talent for monozukuri from an early age. During his childhood in Nakatsugawa, Gifu Prefecture, he discovered a passion for making plastic models.

Kato

I always loved cars. Around elementary school, I got into building plastic models. I still cherish the memory of my Toyota 2000GT model.

Partly on his teacher’s recommendation, after finishing junior high, Kato decided to enter the Toyota Technical Skills High School (now the Toyota Technical Skills Academy).

Kato

My homeroom teacher at the time recommended I take a look at this school. At first, I didn’t think much about it, but being able to earn a salary while studying and getting to work at a car company in the future were very attractive.

After studying at the school from the age of 16, Kato joined Toyota Motor in 1986 and was given a role in finishing and assembling plastic molds. Back then, machining accuracy paled in comparison to today, so most shaping processes were done by hand.

Upon joining the company, Kato was surprised by how much the carmaking genba differed from what he had imagined.

Kato

Before coming to Toyota, I thought I would be working on actual cars. In reality, my work mostly involved grinding blocks of steel or moving heavy objects with a crane. On the production floor, there wasn’t a car to be seen, and my first impressions were different from the job I had imagined.

However, as he watched older colleagues at work, Kato was drawn into the world of mold polishing.

Kato

I was fascinated by the skill of the senior members. Their welding, finishing, and polishing—it was all brilliantly executed. In those days, people didn’t take you under their wing and teach you these techniques, so the only way was to carefully study how the older guys worked. I set out to discover how I could master the same skills.

When it came to honing one’s skills, the trade culture at the time largely embraced an “every man for himself” mentality. Kato closely observed the work of older colleagues, gradually picking up the skills for himself. He recounts one experience, when he was around 25 years old, that left a particularly deep impression.

Kato

While working on a front grille mold, I messed up in a way that couldn’t be redone by machining. To fix it, I ended up shaping the piece entirely by hand. I spent about a month finishing the grille grating, down to the smallest detail.

Those days of grappling with the metal mold brought a major leap in Kato’s skills.

Kato

My supervisor praised me for that, and I started to be known for my polishing ability, which even led to being selected for an overseas assignment.

International experience has been an important part of Kato’s career. He has traveled to production facilities around the world—from North America to the U.K., South Africa, and more—to service and repair faulty plastic molds. In 2016, he was temporarily transferred to China, where he helped train personnel to support a shift to local procurement of plastic molds.

Kato

Overseas, I didn’t have any colleagues to rely on, so I had to solve everything through my own judgment and skills. In particular, since the local molding plants lacked specialized machining equipment, everything had to be done by hand. Succeeding in my work under such circumstances further boosted my confidence as a technician.

When teaching overseas, I would start by demonstrating the key points as we worked through the tasks together. Often, local staff can carry out the basic operations but lack an understanding of the finer details. Having them perform the tasks allowed me to see how much they understood, and then I could teach them the skills they required.

The challenge of paintless bumpers

Around 2020, as part of its efforts to create a carbon-neutral society, Toyota began developing ways of making large parts that do not require painting. The painting process accounted for some 40-50% of the energy used at production plants, and most of that went towards drying. Painting also produces large amounts of waste material, making this an important initiative for reducing both environmental impact and costs.

Kato was approached by Tsubasa Nitta, then at the Production Realization & Production Engineering Division, about a project to make paintless rear lower bumpers for the Crown Sport. Kato embarked on this groundbreaking challenge together with his pupil, Chihiro Takeshita.

Takeshita joined Toyota in 2013, and despite his youth has attained A Level skills, just one rank below Master Instructor.

Paintless technology itself is not new and was already in use for relatively small parts such as B-pillars and exterior trim components. Until then, however, it had never been applied to something as large as a rear lower bumper, where maintaining a uniform surface finish is difficult and even the slightest distortion or blemish easily stands out.

What’s more, the larger the mold size the harder it is to source suitable materials and carry out the polishing process. On the other hand, the advantage of making large parts paintless is a greater reduction in CO2 emissions and costs.

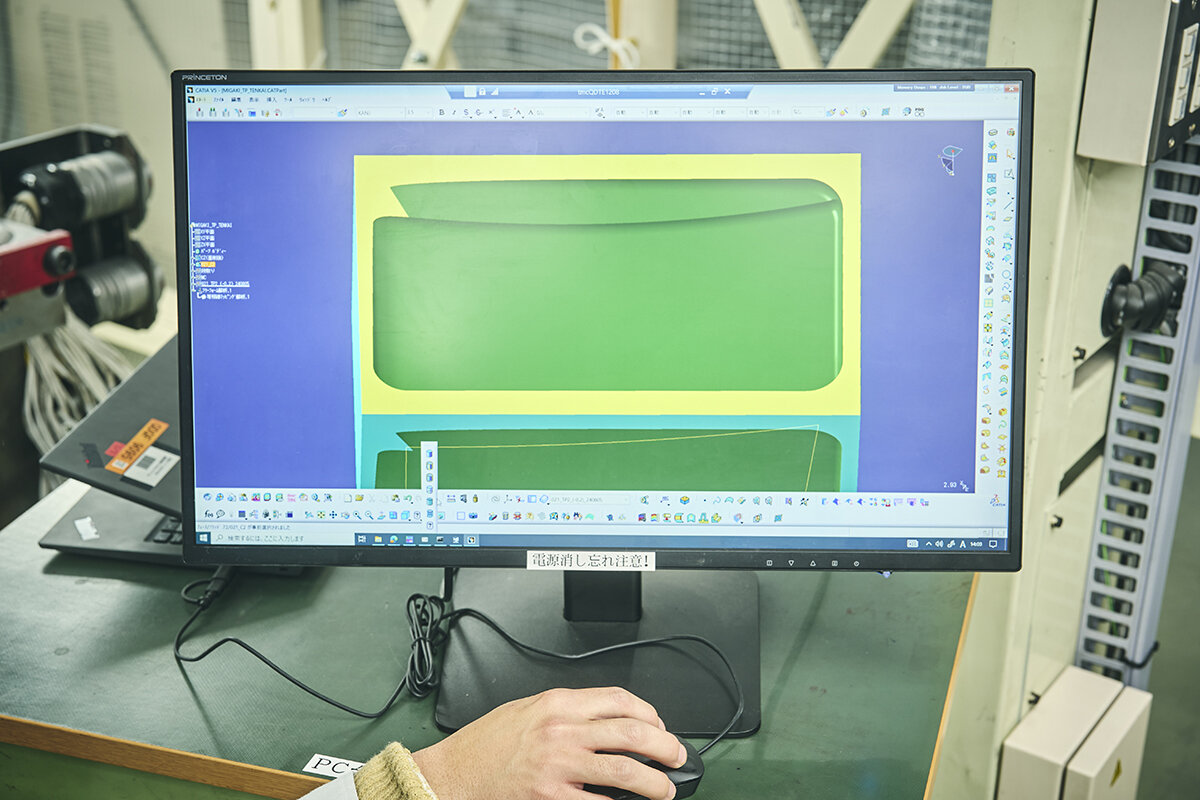

Even with Kato’s mastery of mold polishing skills, the most difficult aspect is accurately crafting the exact forms drawn up by designers. No matter how beautifully the mold surface gleams, it must also be the correct shape to function as a product.

Kato

In essence, our job is to ensure the mold faithfully replicates the shape envisioned by the designer. First, I analyze the mold’s 3D data in detail so that I can visualize the form in my mind. Next, I use my fingertips to feel for slight unevenness in the mold’s surface, and precisely even out the areas needing it with a polishing stone.

Achieving both an accurate form and a beautiful surface finish is extremely difficult, especially for large components.

Kato

When working with larger parts, polishing and reproducing the right shape come into conflict with each other. More polishing gives you a nicer surface, but you also run a greater risk of spoiling the geometry. If you end up with one section slightly sunken, or an edge becomes rounded, you have deviated from the shape the designer intended. Our job is to bring that shape to life exactly as envisioned, while also achieving a perfect mirror finish.

Simply describing the skill involved is a tough ask. When checking the shape of a mold, Kato wears cotton work gloves.

Kato

When looking for unevenness in the mold, we use gloves rather than our bare hands. That thin fabric layer between your fingers and the metal makes it easier to slide your hand along and sense any bumps.

With those fingers, Kato is able to detect surface irregularities of as little as five microns (0.005 mm). He draws on this outstanding sensitivity to ensure each mold is created exactly as the designer intended. The polishing process then removes even finer imperfections, down to around two microns.

In the case of regular painted parts, a few marks on the mold surface do not pose a problem, as they can be concealed by the paint. When you go paintless, however, the mold’s surface texture is directly imprinted onto the resulting component, which means the mold must be polished to a mirror-like finish without a single scratch.

Kato

To create the paintless bumpers, we used forged molds instead of cast molds. When casting a mold, the process of pouring and hardening molten metal creates tiny air cavities. In forging, on the other hand, the metal is pressed, which eliminates such cavities and allows us to achieve a smooth surface finish after machining.

In part two, we discuss how mold materials hindered the creation of the paintless bumper, the 800 hours spent on achieving a mirror finish, and the ways in which Kato’s techniques are being passed on to the next generation.