Our ongoing series looking at the master artisans supporting the automotive industry. For the 21st installment, we spoke with a sheet metal master whose outstanding skills bring car body designs to life with unmatched precision.

Handwork still plays an important role in today’s car manufacturing, even as technology like AI and 3D printing offer more advanced methods. This series features the craftsmanship of Japanese monozukuri (making things) through interviews with Toyota’s carmaking masters.

In this two-part feature, we showcase the Body Manufacturing Engineering Division’s Takahiro Maeda, whose exceptional sheet metal skills make the correction process for stamping dies more efficient, while also helping to craft vehicle bodies with outstanding precision.

#21 Takahiro Maeda, the sheet metal master who creates car bodies with perfect precision

Team Leader, Stamping Equipment Certification Section, Body Manufacturing Engineering Division, Toyota Motor Corporation

Superior skills reduce need for correction

At one of Toyota’s manufacturing skills hubs, located within the Motomachi Plant (Toyota City, Aichi), Takahiro Maeda is working, hammer in hand, to improve the precision of vehicle body parts.

In front of Maeda sits a freshly stamped door panel. Though the part itself looks perfect, when assembled onto the vehicle, it creates slight height differences and uneven gaps with adjoining body panels. This is due to plastic deformation that occurs during stamping and the subsequent hemming process (folding of the panel edges).

Maeda’s role is to correct these minor deformations using his sheet metal skills, in the process of providing data that helps to improve the plant’s stamping dies.

Maeda

Our goal is to ensure that the assembled body does not deviate from the design values, which means eliminating any height differences between panels and making the gaps completely uniform in the finished vehicle. To achieve that, we correct the stamped body parts by hand-working the sheet metal, then feeding the data back to continue improving the dies.

Maeda’s exceptional sheet metal skills have cut down the required die adjustments from around five cycles to just one or two. This not only shortens development lead times but also reduces the cost of correcting dies. What’s more, fewer rounds of revision mean less electricity used in machining the dies and less waste generated, helping to reduce the plant’s environmental impact.

Traditional crafts cultivate monozukuri spirit

Maeda was born and raised in Ishikawa Prefecture, where traditional crafts such as Kaga Yuzen dyeing, Wajima lacquerware, and Kutani porcelain still thrive. His father was a master carpenter.

Maeda

With my father being a master carpenter, I grew up seeing monozukuri in practice from a young age. I think my fascination with precise craftsmanship and making things by hand was born out of this environment.

Maeda’s monozukuri aspirations led him to the local technical high school, where he became immersed in the world of robot sumo. He discovered the joys of combining various components to create a robot.

Maeda

I knew absolutely nothing about the competition, but after a teacher’s recommendation, I tried my hand at robot sumo. The process of assembling a robot part by part could be compared to carmaking, where tens of thousands of components come together into a single product that creates excitement and delight. It made me want to be involved in that kind of monozukuri.

This experience started Maeda on his path to the auto industry.

New employee training reveals budding talent

Upon graduating from high school, Maeda joined Toyota Motor Corporation in 1999. The new employee training provided a significant turning point in his life as a craftsperson. As an introduction to sheet metal skills, the recruits tried their hands at hammering an L-shaped steel plate into a cylinder.

Maeda

At the new employee training, I was the only one who successfully completed the sheet metal task. Based on that result, I was recommended to enter WorldSkills.

WorldSkills is a competition in which young technicians up to the age of 23 pit their talents against each other. Most of Toyota’s participants are graduates of the Toyota Technical Skills Academy, having learned their skills in the company’s carmaking genba from their time as students.

Maeda

Even in our cohort, 90% of the WorldSkills team had come out of the academy, and I was only the third high school graduate.

Having joined the company straight out of high school, Maeda was at a distinct disadvantage going up against academy graduates with hands-on experience. Despite that, he competed in the WorldSkills sheet metal category, winning bronze in his first year and silver in his second.

Indeed, by the time he entered the event in his second year, Maeda already possessed skills worthy of a gold medal. In competition, however, luck also plays a part. Unable to show his full potential on the day, he had to settle for silver. This disappointment drove Maeda to continue improving his skills.

Fortunately for him, being selected for WorldSkills those three years provided him a unique environment, where Maeda was exempted from regular duties and could focus solely on skills training.

Maeda

My three years on the WorldSkills squad were an invaluable opportunity that you rarely get as a craftsperson. It was just like being an Olympic athlete, spending eight hours each day honing my sheet metal skills.

Two skills to master

The sheet metal skills that Maeda sought to master can be divided into two broad categories. One is bending, which entails shaping a sheet by hand over a pipe or other object to create curved surfaces. The other is hammering—striking the metal with a hammer to create the desired three-dimensional forms.

Maeda

Car body parts range from gently curved surfaces to intricate three-dimensional shapes. Only by mastering both skills can you achieve all of the complex forms required.

After acquiring Grade 1 national qualifications in both skill categories, Maeda went on to pass the Special Grade, the highest level. Besides advanced skills, this certification also requires ability in areas such as quality control and problem-solving—truly the mark of a master craftsperson.

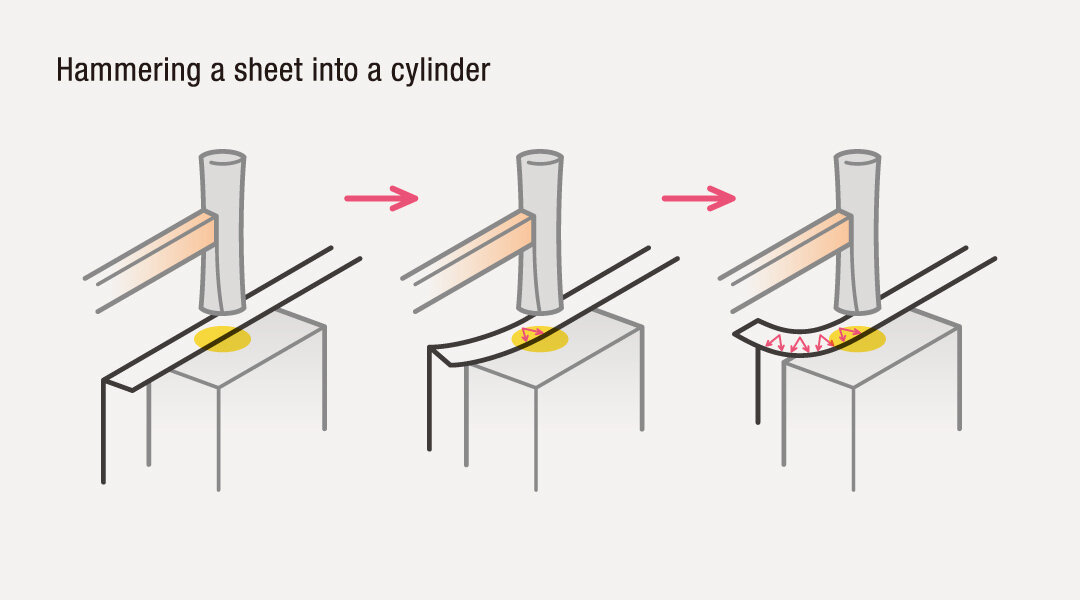

Maeda’s skills have been cultivated over 26 years of on-the-job experience and specialized training for the WorldSkills competition. The level of his expertise is clear to see, even in basic operations. When we visited, Maeda and his pupils demonstrated the task he had performed back in his initial training: hammering an L-shaped steel sheet into a cylindrical form.

Maeda

When you strike the folded edge of the L-shaped sheet, that section will elongate, creating a V-shaped deformation. By doing this consistently and evenly, you can round out the entire piece, creating a cylinder. If the metal is not worked uniformly, you won’t get a perfect circle.

Whereas the technicians in training failed to produce a cylinder despite 30 minutes of trying, Maeda was able to complete one in less than ten. A check with the gauge revealed a near-perfect circle.

The difference in ability can even be heard. Maeda’s hammer work sustains a steady tone, volume, and rhythm, while the blows of his pupils make inconsistent sounds. His hammer moves perpendicular to the metal, shaping it efficiently and producing that crisp clang.

Left hand works with the right

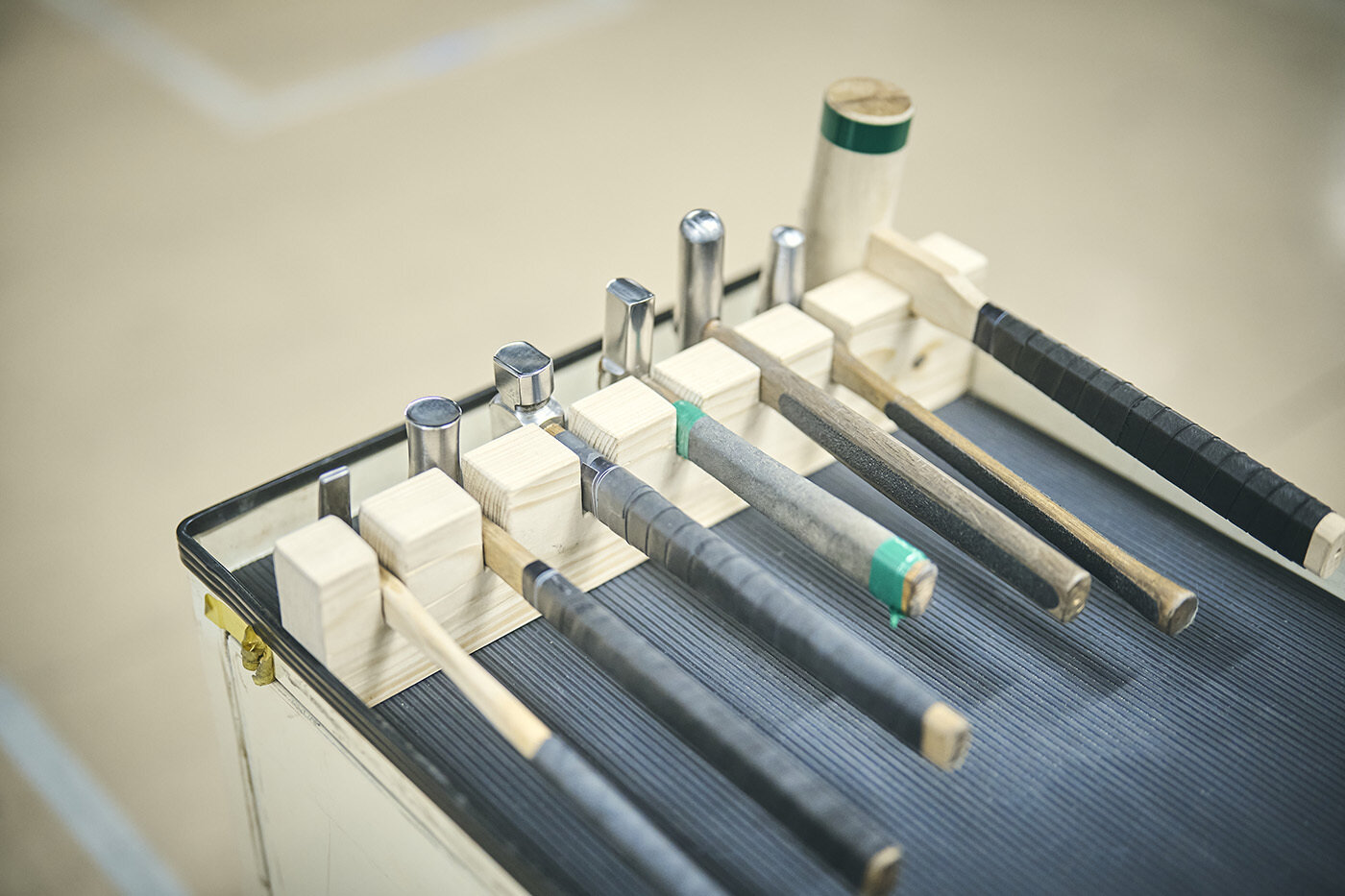

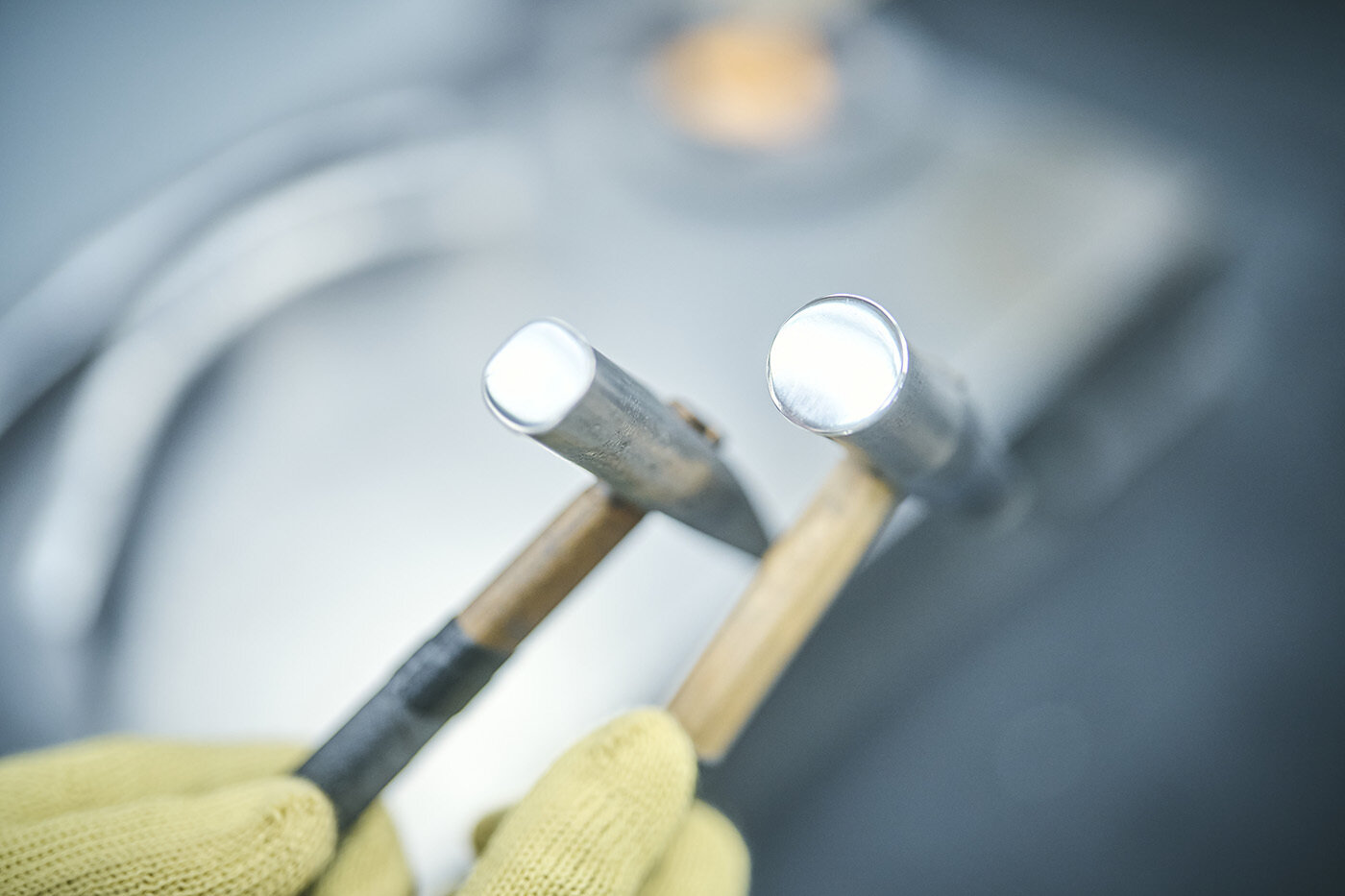

An important factor that underpins Maeda’s abilities is his meticulous care for his tools. The hammers he uses are off-the-shelf products, which he then customizes precisely to suit his needs.

Maeda

The key points for customization are the shape and size of the striking surface. A broader surface area is more efficient at lengthening the metal, but it also requires very precise workmanship.

The way Maeda holds his hammers also stands out: gripping the handle lightly with just the thumb and forefinger, he strikes almost effortlessly, taking advantage of the hammer’s weight and the way it recoils off the metal.

As he explains, the skill lies in each hand carrying out its distinct role.

Maeda

The right hand holding the hammer repeats the same movement, like a machine, while the left hand actually plays the more important role, as it fine-tunes the position and angle of the material.

After so many years of practice, the movements of Maeda’s right hand appear entirely automatic. His attention is concentrated on adjusting with the left, and monitoring changes in the section that he is shaping.

In part two, we will see Maeda’s sheet metal skills in action, crafting body parts to 0.3 mm precision, and explore the need for such mastery as Toyota strives to make ever-better cars.