Our ongoing series looking at the master artisans supporting the automotive industry. For the 22nd installment, we spoke with a "master of winding" whose expertise drives motor development in the era of electrification.

Handwork still plays an important role in today’s car manufacturing, even as technology like AI and 3D printing offer more advanced methods. This series features the craftsmanship of Japanese monozukuri (making things) through interviews with Toyota’s carmaking masters.

In this two-part story, we feature Yoshiki Nagahama of the Powertrain Manufacturing Fundamental Engineering Division. He has spent more than 30 years supporting the development of motor coils that power hybrid (HEV) and battery electric (BEV) vehicles.

#22 Yoshiki Nagahama, The Master of Winding Behind the Heart of the Electrified Era

Assistant Manager, Powertrain Manufacturing Fundamental Engineering Div, Toyota Motor Corporation

The Coils That Define Motor Performance

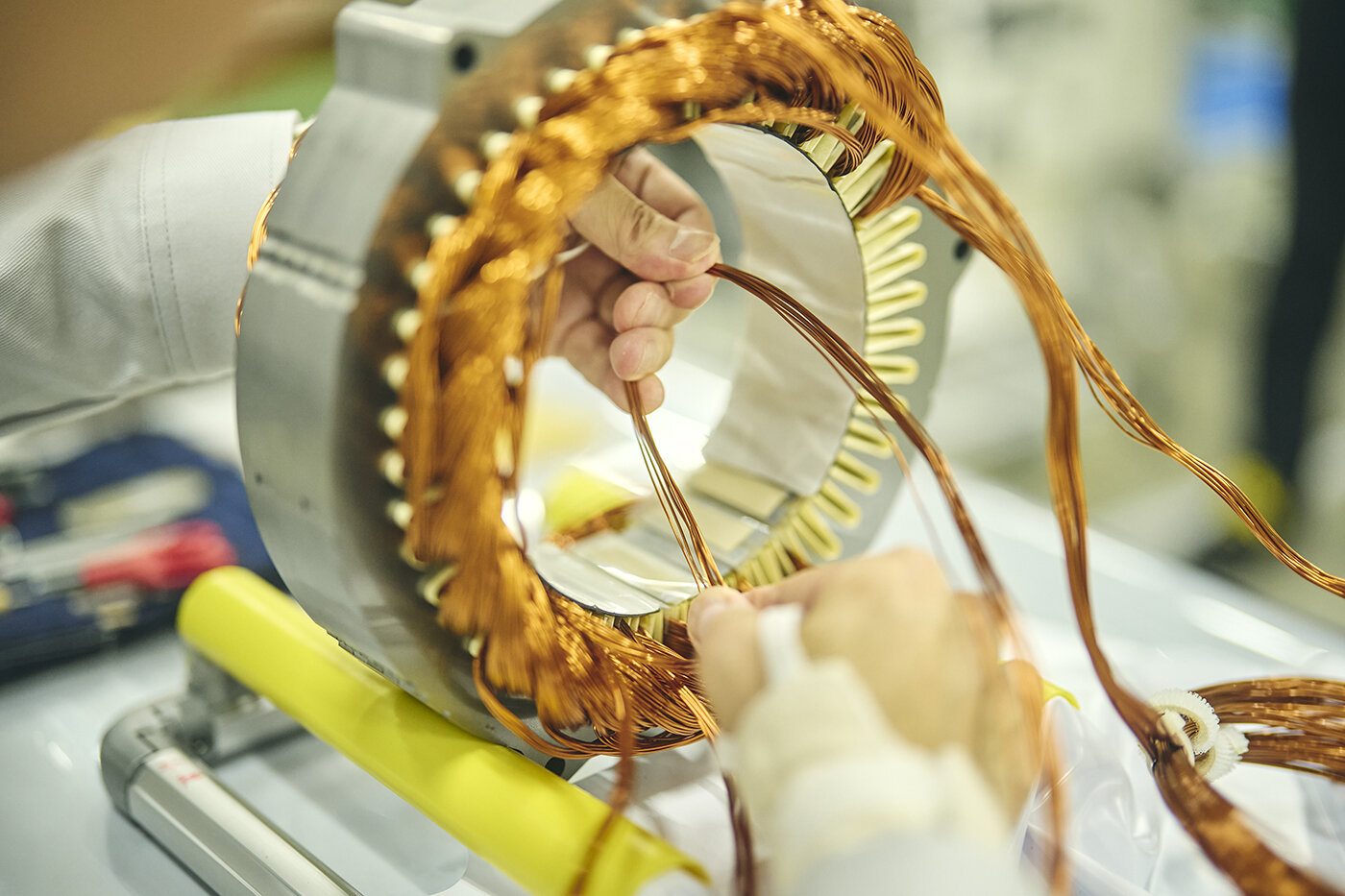

The wave of electrification led by HEVs and BEVs has long since swept through the automotive industry. The performance of the motors that power these vehicles depends largely on the copper coils wound around their stators. For the past 30 years, one master craftsperson has supported the development and prototyping of these windings.

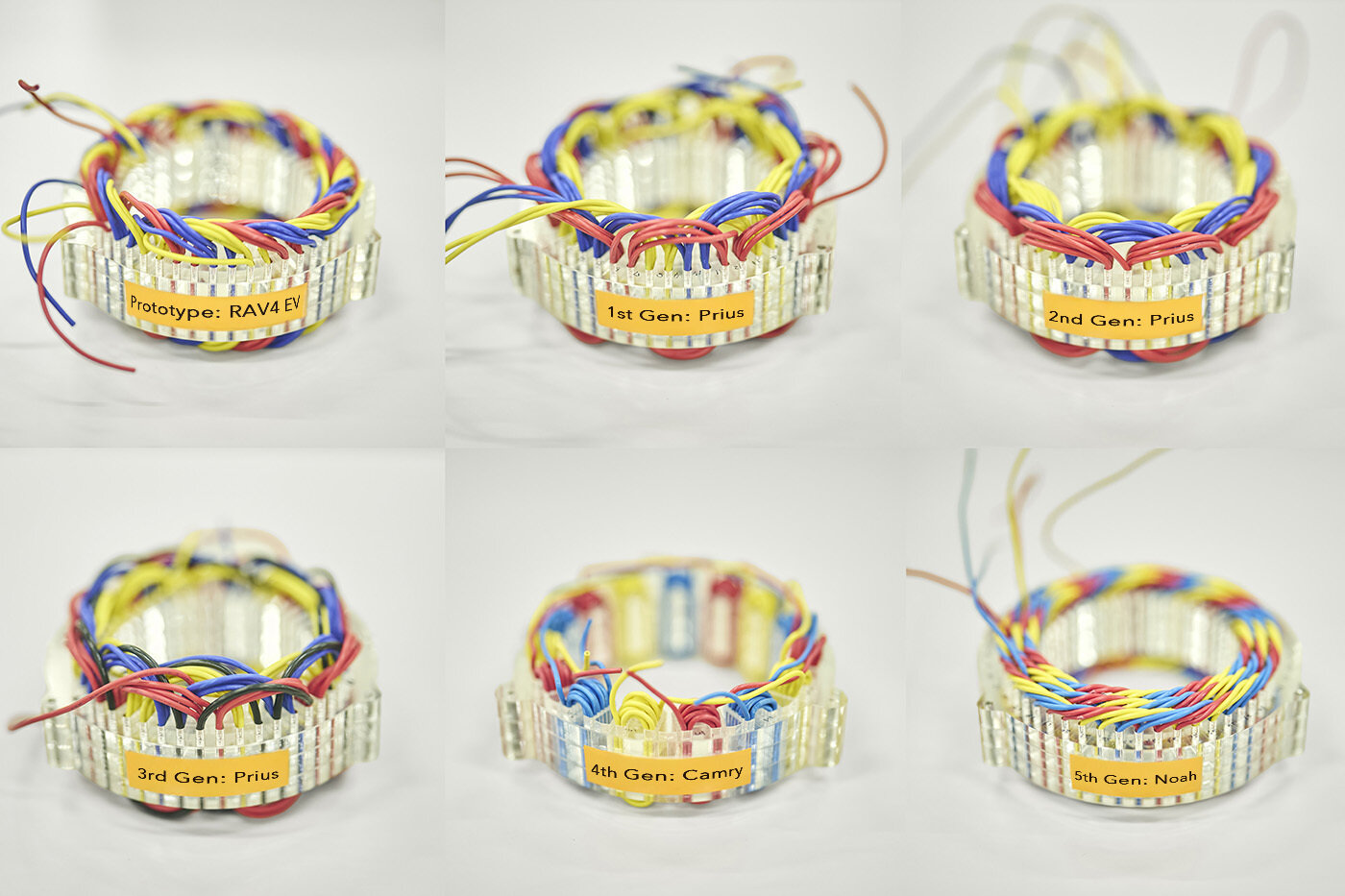

Toyota’s Powertrain Development Building is in the company’s Honsha Plant in Toyota City, Aichi Prefecture. Yoshiki Nagahama joined the company in 1995. Since then, he has supported motor development through every stage of prototyping, from the first-generation motor for Toyota’s first electric vehicle, the RAV4 EV, to the fifth-generation hybrid motor introduced in 2022. He holds an S-Class certification, the company’s highest level of technical qualification.

Nagahama’s work has spanned every stage of motor prototyping, from mastering hand-winding techniques to developing new flat wire production methods and fine-tuning equipment. His skills have become increasingly vital in today’s era of electrification.

What Makes a Motor Turn?

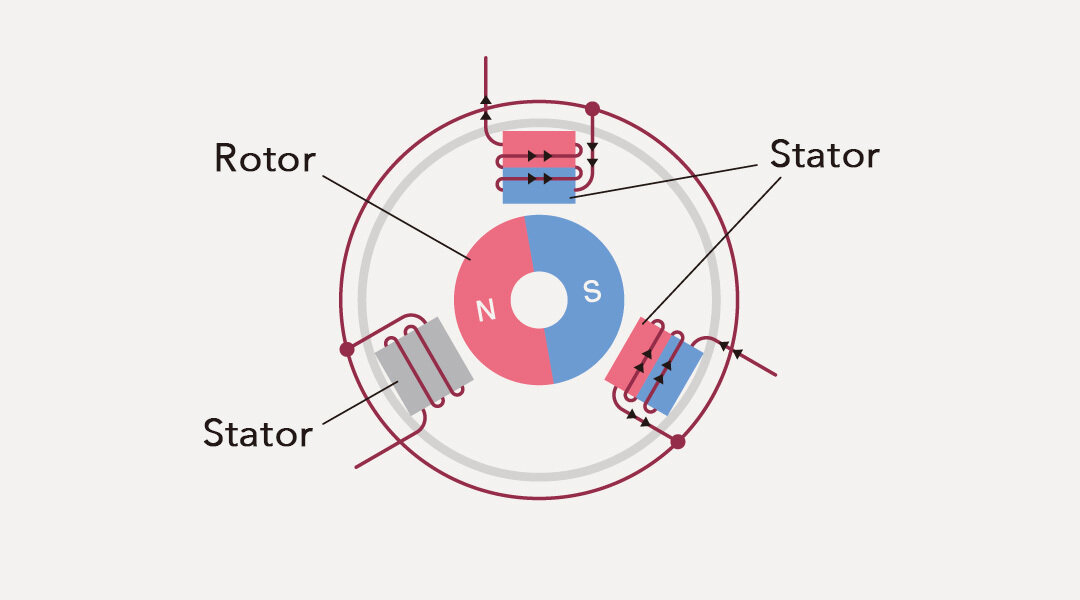

The AC motor which drives the vehicle consists primarily of two components: a stator and a rotor. Copper coils are arranged within the stator, and at the center sits a rotor with built-in magnets.

A magnetic field is generated when electric current flows through the coils. The interaction between the magnetic field and the rotor’s magnets produces rotational force. The way the coils are wound directly determines the motor’s performance.

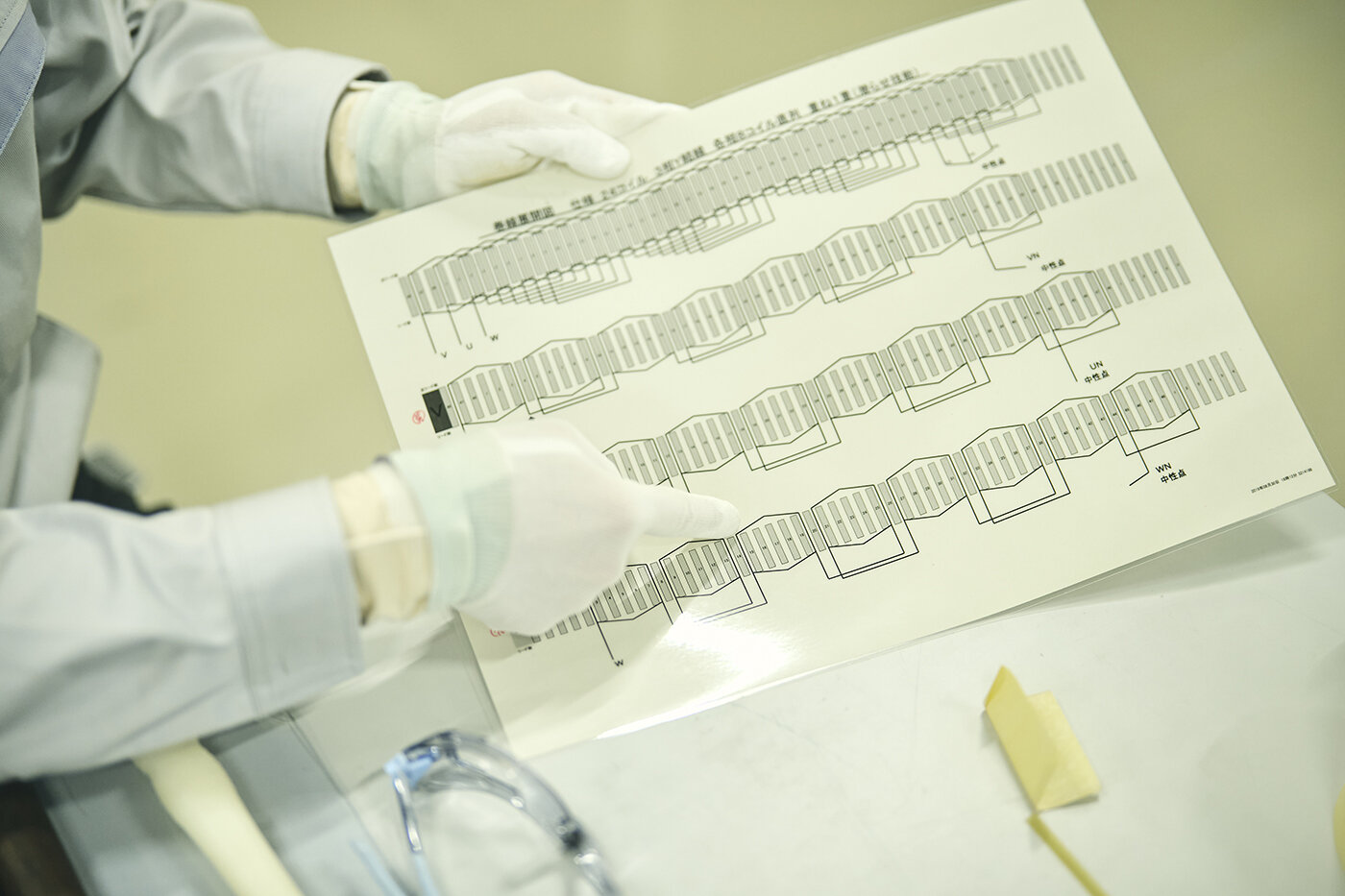

In the Powertrain Development Building, color-coded coil models used to train young engineers are on display. The coils are divided into red, blue, and yellow sections and illustrate the basic structure of a motor.

Most automotive motors are driven by three-phase alternating current. Sending such current into the three U, V, and W phase coils with staggered timing generates a rotating magnetic field. This causes the rotor to turn.

The color-coded model helps visualize how the three-phase coils are arranged. The way these three phases are positioned affects the motor’s power output and energy efficiency.

Nagahama

In fact, a strong magnetic field is generated only within the thickness of the electromagnetic steel sheet. The portions of the coil that extend beyond the steel sheet simply carry current, so the smaller those sections are, the better.

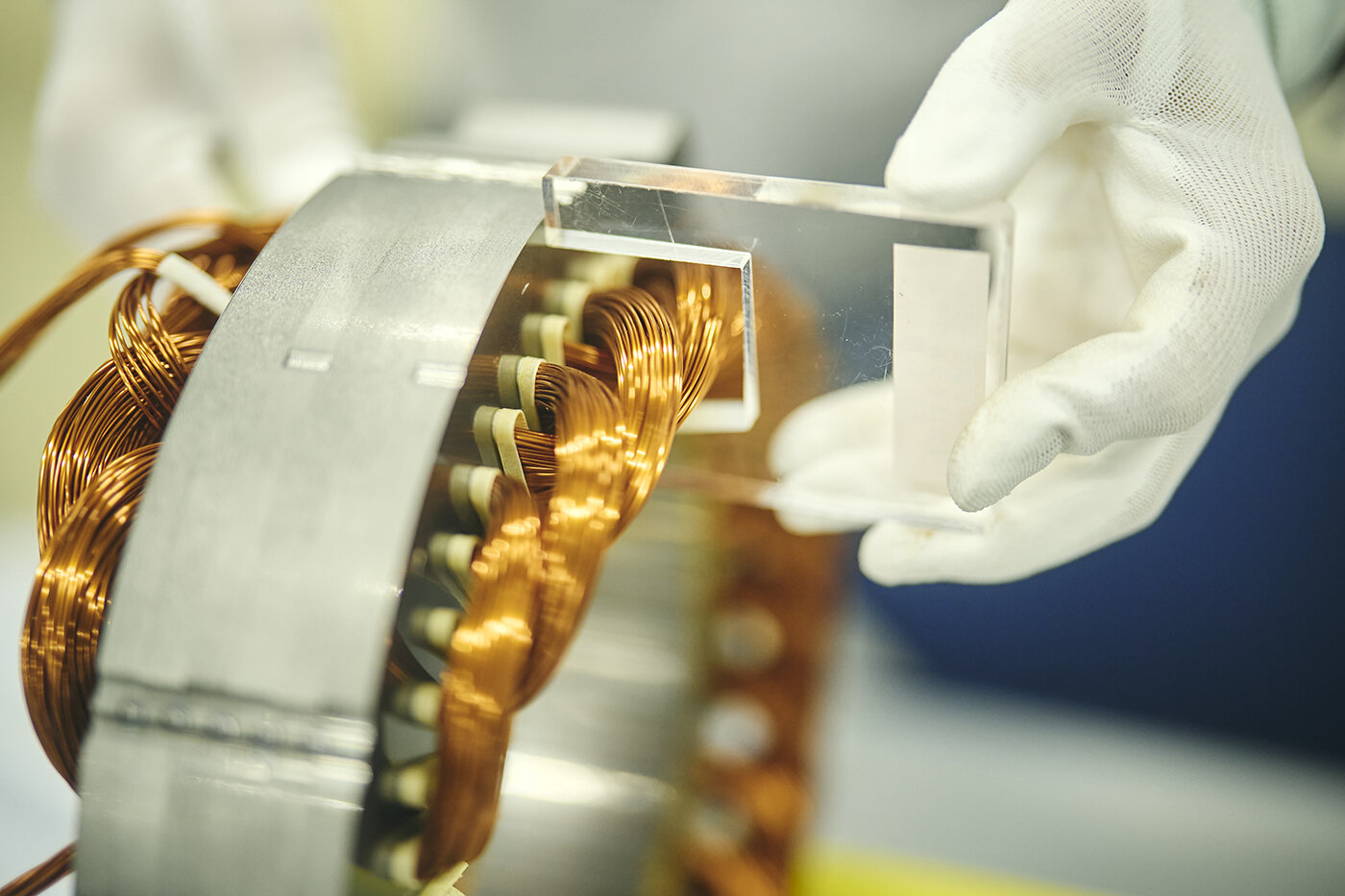

Nagahama uses a specialized gauge to check the size of the coil sections that extend outside the stator during the winding process.

Nagahama

If the copper wires are crossed or scratched and not wound neatly, the current causes heat buildup, which lowers energy efficiency.

The visual precision of the winding directly translates into performance. This is what makes coil-winding such a profound skill.

A Boathouse Childhood and a Culture of Weaving

Nagahama’s roots lie in Ine, a coastal town on the Tango Peninsula in Kyoto Prefecture known for its traditional funaya boathouses. Born into a fisherman’s family, he grew up in a home filled with fishing tools, as his father worked in distant-water fishing.

One technique that Nagahama remembers vividly is a traditional rope-braiding method called Satsuma-ami. It is a complex process in which three additional strands are woven into an existing three-strand rope. The technique is used to splice ropes or form loops.

When he was in junior high school, Nagahama helped repair fishing nets. He wasn’t allowed to handle critical sections that served as the net’s lifelines, but he was entrusted with mending torn nets. What caught his eye was the beauty of the intricately woven mesh.

Nagahama

When I first saw the coil-winding process after joining Toyota, I thought, “This might be something I can do.” The way the coils were wound neatly reminded me of the mesh patterns I had seen since childhood.

Nagahama was the second son in his family. He had already decided to strike out on his own since his older brother was expected to take over the family business. In junior high school, Nagahama’s [JR1.1]passion for basketball sparked an interest in Panasonic, known at the time for its strong corporate basketball team.

Nagahama chose to study electrical engineering in high school. There, he came across a brochure for the Toyota Technical Skills Academy. The program offered practical skills training along with a salary that could help repay his three-year high school scholarship. It also promised a future career at Toyota. Encouraged by his homeroom teacher, Nagahama decided to enroll in the academy.

Taking on Toyota’s First Electric Vehicle

Nagahama joined Toyota Motor Corporation in 1995. He was assigned to a department that manufactured small in-house motors for automated guided vehicles, or AGVs, and similar applications.

Soon after joining the company, Nagahama came across an opportunity that would shape his future. A new project had just begun: the development of the motor for Toyota’s first electric vehicle, the RAV4 EV.

There was no other department within Toyota capable of producing drive motors. Nagahama’s team was chosen because only their division possessed the skills required to hand-wind coils.

From that point on, Nagahama spent every day winding coils. The guidance from his senior colleagues was relentless.

Nagahama

Sometimes when I came in to work in the morning, I found coils that I had finished winding the day before had been thrown away. If they failed inspection and were deemed unusable, I had to start over from scratch.

Why was the process so strict? There was a reason for this. The enameled copper wire that makes up the coil is coated with a 42-micrometer insulating layer. A slight scratch on that coating cannot be detected through standard inspections that measure resistance or insulation. Such tiny flaws can escape notice.

A destructive test was required to test for scratches. The coil was submerged in a special saline solution to see if the liquid would seep through any damaged areas. However, as the name suggests, it was a destructive test, and the coil could not be used afterward.

Nagahama

I learned to take full responsibility for completing my part of the process. Work done without thorough quality assurance can lead to defective parts going on to the next process. Attention to that risk was drilled into me.

If a damaged coil made it into a vehicle, it could generate heat during use and, in the worst case, catch fire. That is why senior technicians were so strict with their training.

Nagahama gradually built up his skills through repeated mistakes and countless do-overs. The rigors of his training instilled the fundamentals of hand-wiring. Yet this was only the beginning of what would become 30 years of continuous mastery.

An Artisan’s Sense Beyond Words

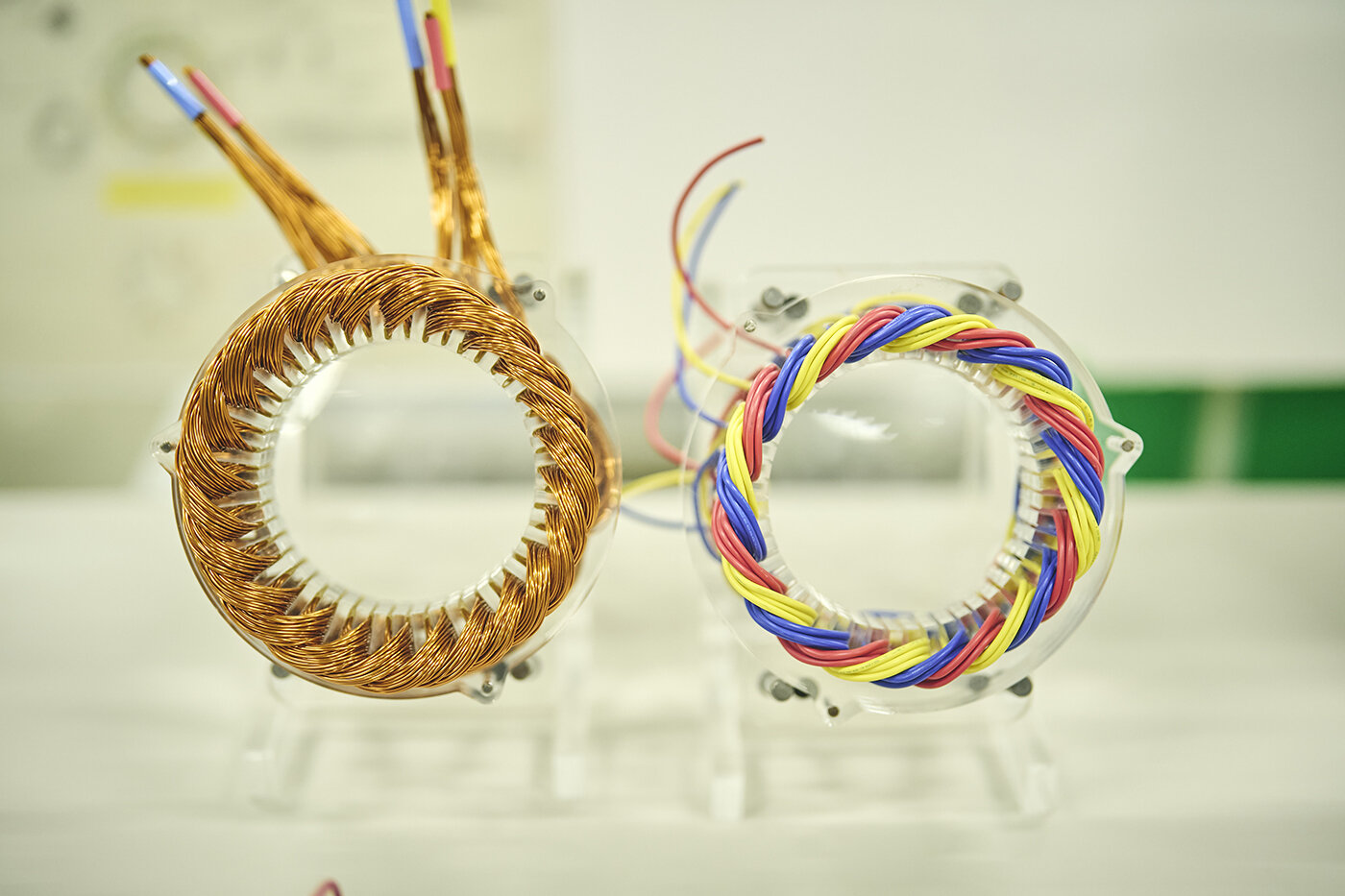

What lies at the heart of hand-winding skills? It is a delicate sense of touch in the fingertips, something that cannot be fully explained in words. The stator has grooves, called slots, carved in a radial pattern, and the copper coils are wound into these slots. For this task, Nagahama uses a tool he calls a “comb.”

Nagahama

I use this comb to align the coils inside the slots. My own creation, cut at an angle and polished smooth to prevent it from scratching the copper wire.

Nagahama made this tool himself. By shaving the tip of the comb at an angle, he can apply just the right amount of force without damaging the copper wire or its insulation.

When winding, it’s important to constantly sense how the copper wire is behaving. The wire gradually twists as it is wound. If these twists are left unchecked, the wire will kink and cannot be wound neatly.

Nagahama adjusts for the twist by rotating the bucket that holds the copper wire bundle to the right and to the left. In this way, he controls the natural curl of the wire and maintains it in optimal condition.

Copper wire is a delicate material. It is easily scratched, and repeated bending causes it to harden and become brittle. This is why it is crucial to apply just the right amount of force without putting stress on the wire.

Nagahama did not learn these skills through verbal instruction. He observed his senior colleagues’ work closely and refined his technique through repeated trial and error.

“I learned by watching, and I even came up with my own tool designs,” Nagahama says with a smile. At the time, the prevailing culture in craftsmanship was that you had to improve your skills on your own. Within that environment, he honed his technique through repeated mistakes. As his experience grew, his senses became more refined.

Nagahama

I can tell whether the coils are properly aligned from the sensations coming through the tools to my hand. When I pull slowly, there’s a distinct feeling that tells me they’ve settled neatly into place.

This is the essence of craftsmanship. It cannot be quantified or fully expressed in words, yet it undeniably exists and plays a vital role in supporting motor performance.

Facing the Challenge of Mass Production with the First Prius

In 1996, Nagahama became involved in another major project following the RAV4 EV. It was the development of the motor for the world’s first mass-produced hybrid vehicle, the first-generation Prius.

Because the RAV4 EV was produced in small numbers, all the coils could be wound by hand. But the Prius was designed for mass production, and hand-wiring could not keep up. Every step of the process had to be converted to machine-based manufacturing.

The method adopted was known as “lacing.” In this approach, the section called the coil end is preformed to the specified dimensions and then bound with insulating thread. The continuous movements of lacing with a special hook require precise control of factors such as hook height, angle, and thread tension, which are programmed into the equipment. In this way, the finalized manufacturing conditions were gradually transferred, step by step, into the motor production line. As this shift progressed, the work itself began to evolve from one-off craftsmanship to mass production.

Nagahama

To wind coils by machine, the winding method itself must be suited for machine operation. So first, we manually reproduced the lacing method and established the right conditions. We then programmed those parameters into the equipment to enable mass production.

Takeshi Uchiyamada was the chief engineer in charge of developing the first-generation Prius and would later become chairman of Toyota Motor Corporation. At the time, he frequently visited the prototype workshop. He often asked Nagahama and his colleagues,

“Can you add one more turn to the coils?”

Uchiyamada pushed to see if the number of coil windings could be increased to further improve performance. His determination left a strong impression on the technicians at the site.

In 1997, the company launched the first-generation Prius, and it went on to make automotive history as the world’s first mass-produced hybrid vehicle.

Looking back with nostalgia, Nagahama recalls feeling a sense of accomplishment at the time. Yet soon after, he would experience a setback.

When mass production of the Prius began, Nagahama was assigned to support the production line. What he encountered there was a world entirely different from the prototype workshop.

Nagahama

At that time, I didn’t understand the equipment or the manufacturers that built it. I could speak about what mattered from a product standpoint, but that wasn’t enough to meet the needs at the production site.

This experience became a major turning point for Nagahama. He came to understand that the role of prototype development was not simply to create prototypes. It also included establishing the conditions needed for equipment to operate reliably in mass production.

Nagahama

I learned that manufacturing and setting the right conditions must be perfected together. To achieve that, close collaboration across teams is essential.

The prototype team, the production team, and the equipment manufacturers must all work together to create a good product. Nagahama learned this essential truth from his setback on the production floor.

In the second part of this feature, we explore the technological shift from round to flat wires, a return to hand-winding after ten years, and the passing on of craftsmanship to the next generation.