Our ongoing series looking at the master artisans supporting the automotive industry. For the 22nd installment, we spoke with a "master of winding" whose expertise drives motor development in the era of electrification.

Handwork still plays an important role in today’s car manufacturing, even as technology like AI and 3D printing offer more advanced methods. This series features the craftsmanship of Japanese monozukuri (making things) through interviews with Toyota’s carmaking masters.

In this second installment, we feature Yoshiki Nagahama of the Powertrain Manufacturing Fundamental Engineering Division. He has spent more than 30 years supporting the development of motor coils that power hybrid (HEV) and battery electric (BEV) vehicles.

#22 Yoshiki Nagahama, the Coil-Winding Master Driving Agile Development

Assistant Manager, Powertrain Manufacturing Fundamental Engineering Div, Toyota Motor Corporation

From Round to Flat Wire: A Wave of Technological Innovation

In the 2000s, a new phase of motor development began. The ambitious goal was to make the motors more compact while increasing output and reducing costs.

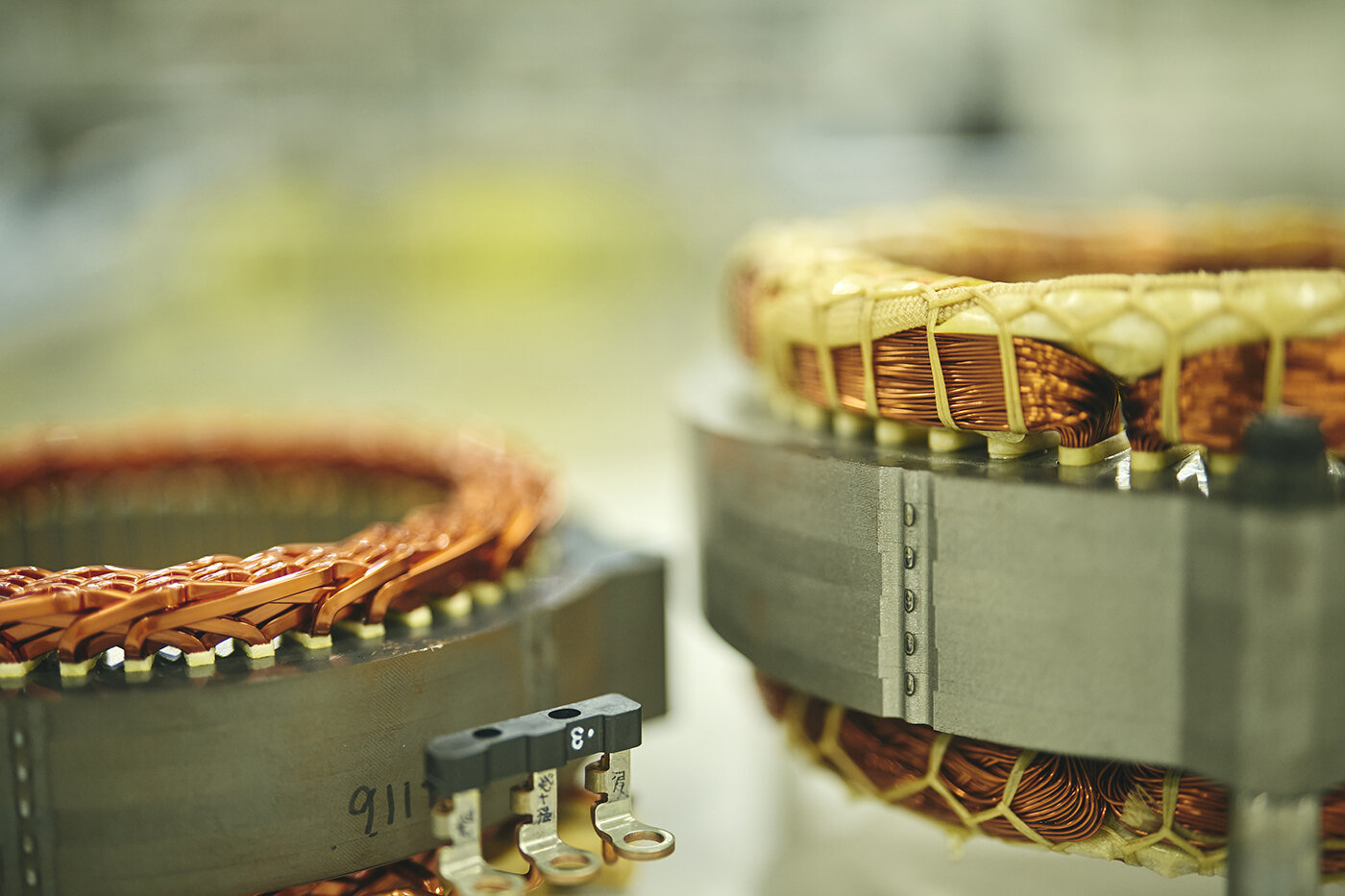

The key to achieving that goal was a new technology called SC (Segment Conductor) winding, which replaced conventional round wire with flat wire.

With conventional round wire, the circular cross-section leaves gaps between the coils. These gaps are wasted space that does not contribute to magnetic field generation. The space factor, or the proportion of copper within the coil’s volume, was around 40%.

Flat wire, on the other hand, has a rectangular cross-section, which allows the coils to be packed tightly without gaps. This increases the space factor to about 60%. Fitting more copper into the same volume allows a stronger magnetic field to be generated. Toyota was among the first in the industry to adopt flat wire for hybrid motors.

However, with flat wire, the process changed from “winding” to “assembly.” Straight copper wires are press-formed in a mold and bent into a U-shape, then inserted into the stator one by one.

This greatly improved production efficiency but also changed Nagahama’s role. Opportunities for hand-winding decreased, and his focus shifted to developing the flat-wire manufacturing process. He began working on mold and jig production as well as equipment adjustments, marking the start of a new set of challenges in the prototype workshop.

Nagahama

We check for any bulges or scratches that may appear when the flat wire is bent. To ensure that each piece meets the precise specifications shown in the design drawings, we also established a method for evaluating the shape.

The knowledge Nagahama had gained through hand-winding proved valuable here as well. He knew where the wire was most likely to be damaged and how to shape it without putting stress on the copper. His experience became the foundation for developing the flat-wire manufacturing process.

After 2010, prototype development fully transitioned to flat wire. Nagahama continued to play a central role in prototyping and development, but opportunities for hand-winding had become rare.

It was around this time that a concern began to take root in Nagahama’s mind: the passing down of craftsmanship. The hand-winding skills he and his colleagues had spent decades perfecting might no longer have a place in the future. He began to wonder whether they were still worth passing on.

The answer would come in an unexpected way.

A Return to Hand-Winding After 10 Years

In 2020, Nagahama received an unexpected request from the Higashi-Fuji Technical Center. They asked him to hand-wind coils for the development of an induction motor.

An induction motor has a different structure from the permanent magnet synchronous motors used in HEVs. It operates without magnets in the rotor. Instead, a rotating magnetic field in the stator induces current in the rotor, and the magnetic field generated by that current causes the rotor to turn. Because it does not use rare earth materials, it offers the advantage of reducing resource-related risks.

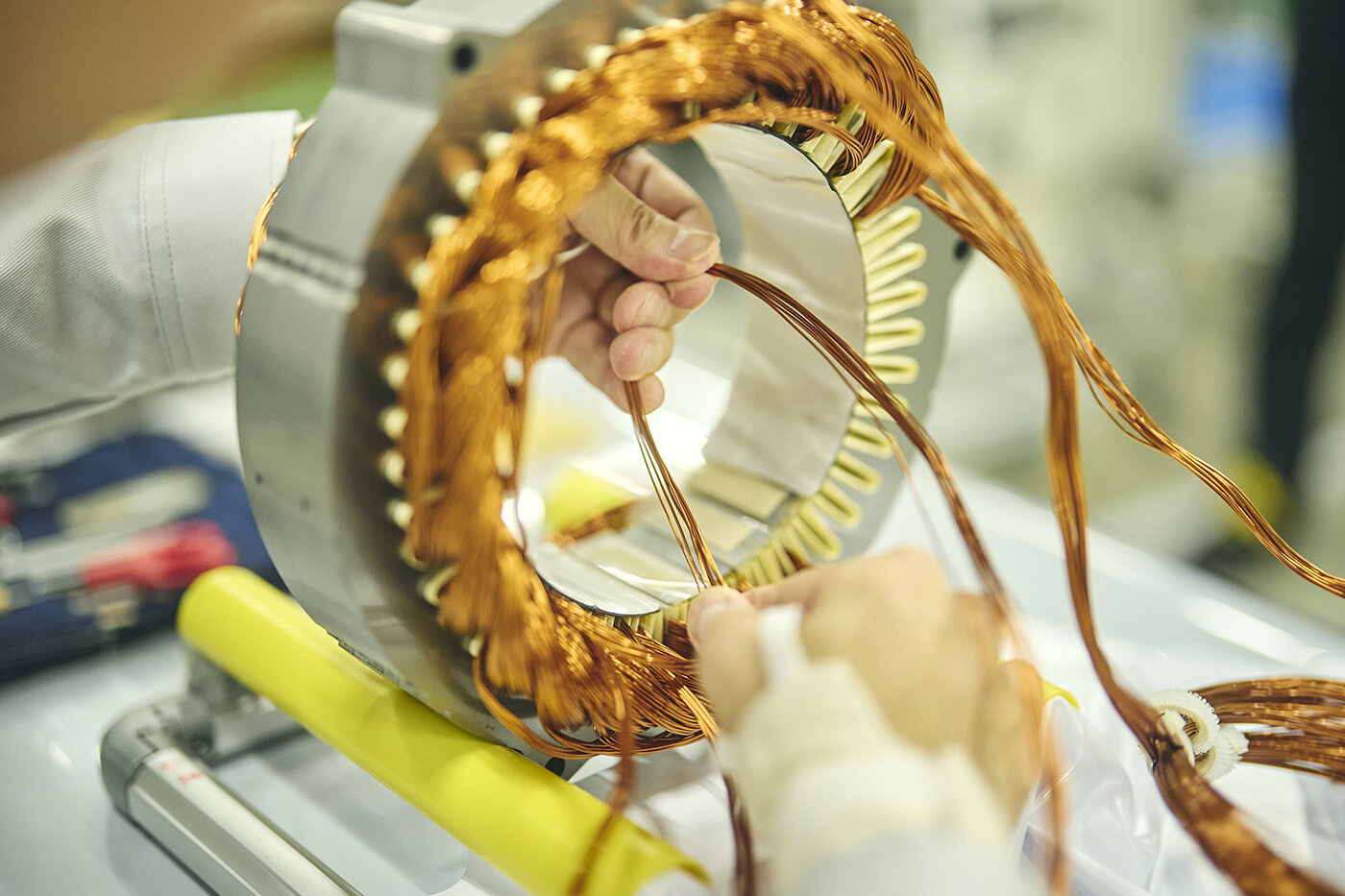

Nagahama’s hand-winding skills were once again needed for the induction motor prototypes. Ten years had passed since he last performed the task, yet as soon as he began working, his hands remembered. The sensations in his fingertips, the way he used the tools, and how to handle the copper wire all came back to him. The skills he had acquired over three decades had not faded.

How Hand-Winding Skills Add Agility to Development

Nagahama worked closely with the design team in developing the induction motor. Requests came one after another: “We want to change the number of coil windings,” “Can this single prototype handle multiple evaluation patterns?” “Can the delivery schedule be moved up?”

Flat wire is normally formed using molds. When specifications change, sometimes the molds need to be remade. In the early stages of development, where specifications are frequently revised, constantly remaking molds is too expensive and time-consuming.

With hand-winding, however, changes could be handled flexibly. Nagahama would adjust the conditions manually to make the prototypes and could complete a new coil with the revised specifications by the next day.

Nagahama

I can respond right away, even if there is a design change. That’s the advantage of hand-winding.

Hand-winding allows for immediate adjustments that would be impossible with flat wire production. In the early trial-and-error stages of development, this flexibility becomes a powerful advantage for agile development.

The coils Nagahama produced are passed to the motor designers for performance evaluation. Based on the data, new ideas for improvement are discussed, and updated specifications are then sent back to Nagahama. Repeating this cycle many times reveals the optimal design. For the technicians involved, this process also serves as a valuable challenge and an opportunity for growth.

Nagahama

The role of prototyping is to quickly give form to the ideas envisioned by the designers. Having hand-winding capability greatly expands freedom in development.

The Value of Hand-Winding in the Flat-Wire Era

The transition to flat wire brought dramatic improvements in motor performance and productivity. At the same time, however, it also introduced limitations to flexibility in prototype development.

Through his experience with induction motor development, Nagahama reaffirmed the value of hand-winding skills. Even while aiming for mass production with flat wire, he performs prototype winding by hand in the early stages. This hybrid approach makes efficient development possible.

Nagahama’s understanding of both hand-winding and flat-wire technologies enables him to serve as a bridge between design and production. He translates the conditions established through hand-winding into a process suitable for flat-wire mass production. His knowledge supports the smooth transition from prototyping to full-scale manufacturing.

Nagahama

My experience with hand-winding helps me understand where to be careful when working with flat wire, such as where the copper becomes stressed and where scratches are likely to occur. That kind of insight directly contributes to developing flat-wire production methods.

Even as technology evolves, the fundamental principles honed through hand-winding remain unchanged. Preventing damage to the insulation, aligning the coils beautifully, and drawing out maximum performance are essential across every production method.

Passing Down the Craft

Nagahama’s experience developing the induction motor reaffirmed the importance of passing on technical skills.

Nagahama

This skill could disappear after I retire. I began to wonder if that would be acceptable. More than ever, I started thinking about what I could do to keep it alive.

The thought motivated Nagahama to begin focusing on training younger technicians. Yet passing down hand-winding skills is no easy task.

Nagahama grew up in a culture where one was supposed to “learn by watching.” He understood how difficult it is to explain craftsmanship with words. The subtle pressure of the fingertips, the angle of the tool, the adjustment of the copper wire’s twist—all belong to the realm of a craftsperson’s intuition and feel.

Even so, Nagahama kept searching for ways to teach. He first demonstrated his process to younger workers and then had them try it themselves. He encouraged them to repeat it without fear of failure.

Nagahama

It never goes well at first, and that’s perfectly fine. You learn the most from mistakes.

Just as he once learned by observing his seniors and refining his own tools, Nagahama now passes those lessons on to the next generation.

A Craftsperson’s Vision for the Future

Nagahama is now in his fifties and has a little over ten years until retirement. Even as he continues efforts to pass on his skills, his curiosity and drive remain as strong as when he first joined Toyota. For thirty years, his focus has been unwavering: creating better motors.

The wave of electrification continues to accelerate. As BEVs become more widespread, the demand for motors keeps rising. With that, coil-winding craftsmanship is becoming valued once again.

Nagahama

Electrification has only just begun. In the years ahead, motors will need even higher performance. I look forward to seeing how my skills can contribute to that.

The boy who grew up in the fishing town of Ine, surrounded by a culture of weaving nets, became a master of winding copper wire at Toyota. Over thirty years, from the RAV4 EV to the first-generation Prius and the latest motor designs, the number of coils he has wound is countless.

The technology has evolved from hand-winding to flat wire coils, but the essence of Nagahama’s craftsmanship remains unchanged. He gives form to the ideas of designers and paves the way toward mass production. As electrification continues to advance, the skills of artisans like Nagahama in the prototyping process will remain indispensable.