Our series showcasing Toyota's activities in non-automotive fields. Today's topic: carnivorous pitcher plants!

“Toyota is doing what?!” Last year, one of the company’s research projects went viral, being shared more than 1.3 million times on social media. The subject? Tropical pitcher plants.

Curiosity piqued, we went to investigate, only to find ourselves in a room full of foliage.

What on earth was going on…?!

Could this research be too far outside the box?

The place we visited was Toyota Central R&D Labs, established jointly by members of the Toyota Group.

Aside from developing automobile-related technologies, the labs carry out fundamental research toward a sustainable society across a wide range of fields, including resource conservation, energy efficiency, environmental protection, and improved safety.

For the past decade or so, researchers have also sought to learn from nature, with the pitcher plant project falling under this umbrella. The greenery-filled room mentioned above is related to Genki-Kûkan™, which we previously showcased on Toyota Times. In case you missed it, we’ll have more on this fascinating initiative later in the article.

First, we had to ask the obvious question: why pitcher plants?

Dr. Satoru Machida, Senior Researcher, Quantum Devices Research-Domain, Toyota Central R&D Labs

One day we were looking for a research subject when someone suggested, “Let’s go to Higashiyama Zoo and Botanical Gardens!” So off we went like a field trip.

The staff showed us pitcher plants, carnivorous species with bulging round pouches. We received some as a souvenir, and when we got back to the lab, we immediately started slicing them up to examine under the microscope.

That’s no way to treat a souvenir! Yet as Dr. Machida tells, this yielded some astonishing findings.

Incidentally, pitcher plants are so named because of the pouches they use to trap prey, which resemble pitchers—of the liquid-holding rather than the baseball-playing variety. The lab’s other efforts to glean lessons from nature have focused on questions like “Why do gecko feet stick to walls?” and “How do four-legged animals run?”

Some dinosaur buffs among the researchers even looked into the skeleton of Quetzalcoatlus, said to have been the largest flying reptile. Another study related to animal bones led to the creation of this chair:

Lightweight without compromising durability, it has the potential to be used for car seats.

When adult researchers get to throw themselves wholeheartedly into kids' science projects, amazing things happen. Though some of their work struck us as rather odd, we had to tip our hats to the team!

What are these weird bumps?

Let’s get back to our pitcher plants. As the team examined their specimen from top to bottom, something caught their attention.

Dr. Satoru Machida, Senior Researcher, Toyota Central R&D Labs

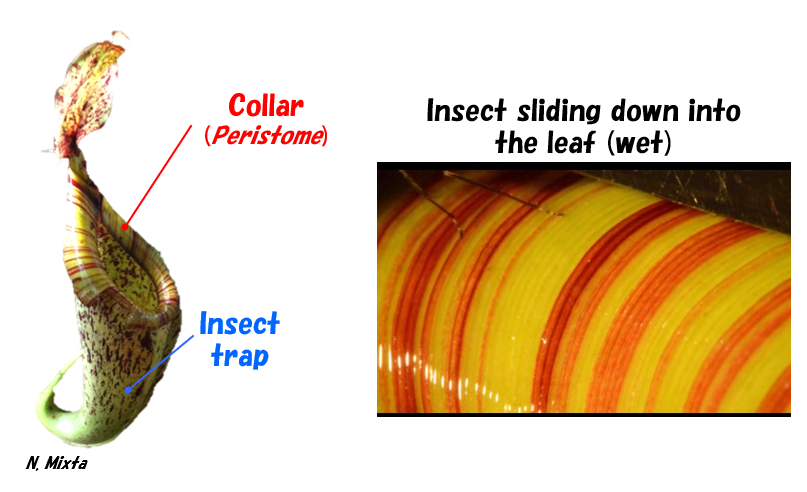

The pitcher plant’s collar is shaped so that insects landing on it slip down into the trap, and we noticed that this collar has a very intricate structure.

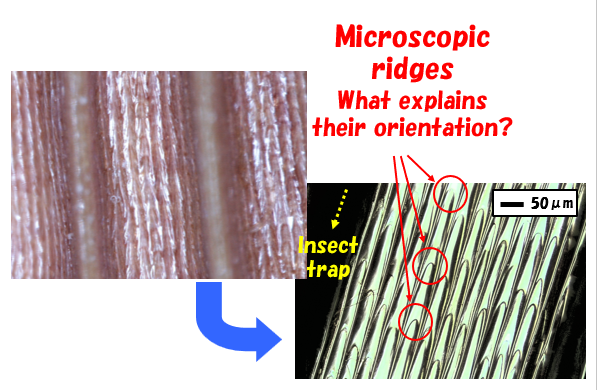

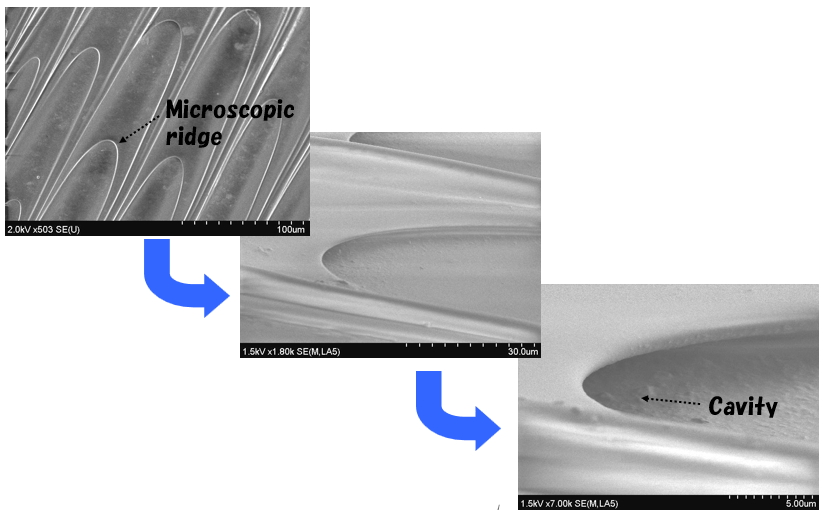

We even brought out the electron microscope to really examine the surface, and that revealed tiny ridges, all facing in the same direction.

We knew there must be a reason. While botanists focus on classification, as engineers we have an eye for functions and structures.

Viewing the collar at an angle revealed a three-dimensional aspect, with cavities beneath the ridges.

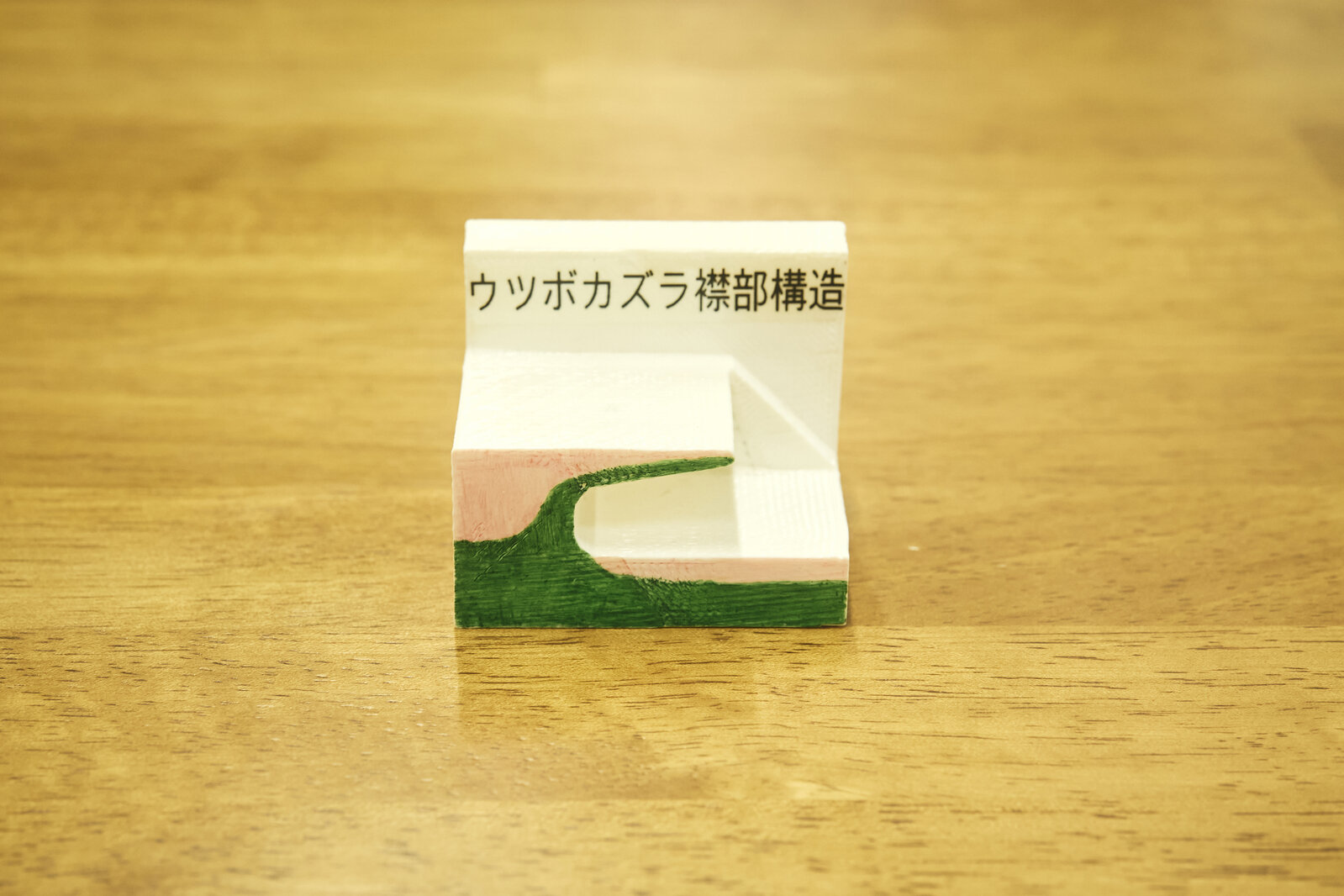

Upon closer examination, the analysis team found that the ridge extends sharply outward like an awning, as in the model below. By this point, they were convinced that this structure must hold some kind of function.

In such situations, researchers from different fields come jumping in, eager to solve the mystery. One expert on surfaces suggested using a dropper to run water over the area. Here is a video of that experiment.

When water is flushed over the collar from inside to outside, it flows smoothly. Going the opposite way, however, the flow of water is obstructed. In essence, the collar of pitcher plants allows water to flow freely in one direction, but not in the other.

It’s tempting to assume that this is due to the cavities catching the water, but in fact the very opposite is true—water flows more easily when it has to climb over the ridges. Why?